Our next surprise was the fact that, though the house was built with the bricks laid directly on the hard Virginia red clay, with no poured foundation (as was a traditional construction technique used during the time it was built), the interior brick walls flanking the main hallway were laid on a huge wooden beam set onto the clay. This served well over the ensuing century, as the soil below was dry, having a roof set overhead, so the beam sat unyielding all those years. The fire, however, had its way with the wood, and the beam on the South wall had disintegrated altogether. The entire weight of the brick wall traveling from the basement to the top of the second floor was resting its entire weight on a single brick that had fallen into the space where the beam used to be, and the wall was already starting to give in to the pressures of gravity, the sag in the adjacent attached stud walls showing evidence of this slow downward descent. This was the internal backbone of the house, with all of the floor joists joining into and depending upon this sturdy structure. The house was slowly collapsing in upon itself.

Emergency measures were taken to create a support system to first take the weight of the third floor off the second floor, then take the weight of the second floor off the first floor, then to support the first floor itself, before jacking that three-story brick wall back into place slowly and pouring it a new concrete foundation. We used a large chunk of our anticipated budget in this first unexpected expense.

The roof was gone completely, and in danger of collapse, so we hastily documented the slate patterns before taking down what was left that could not be salvaged, and went about the business of finding a good roofer. In the meantime, we learned about a relatively-new product for roofing. The SIPS panel. It is a Styrofoam bed sandwiched between two sheets of plywood. It holds the highest R-value of any structural material currently on the market. We also got approval to be able to insulate the perimeter brick walls of the home from the Virginia Department of Historic Resources (DHR). Previously, the plaster had been applied directly to the exterior brick walls, providing no insulation. Thus began our journey to create an oxymoron: an energy-efficient Victorian home. Instantly, more money began pouring out of our pockets and disappearing from our checking account.

Once the debris was cleared, and the floors supported so they could be safely traversed, we began to get to know the house a little better, and began to appreciate some of its finer points. The view from the second floor out of the rear of the house was beautiful, and with the main floor rear porch, elevated as it was, a lovely back yard beckoned.

The main hallway, cleared of debris, was more than ample, and the general floor plan was simple, yet had a nice flow from one room to another. Generous ceiling heights and large doorways allowed the light from abundant windows to reach to all corners of the rooms, so that in daylight there really was no need for supplemental light sources.

We broke through a shallow closet in one of the second-floor bedrooms to discover an empty space above the dining room that would allow us to create a bathroom and walk-in closet in a space that had been previously never accessible.

We opened up rooms back to their original dimensions, removing small storage rooms and bathrooms that had been added along the way.

Since the structure was unsound anyway, we tore it off, in anticipation of either having to re-build it as it had been, or, hopefully to be able to expand it into an expansive eat-in kitchen below, a master suite in the basement beneath that, and a second floor master suite above. We would wait a while before presenting this to the DHS Architect, and gather our ammunition for the proposal.

In the meantime, it stood as a giant gaping hole on the rear of the house until its fate could be decided.

We also removed the extra “front door” from the Music Room and restored it back to its original configuration as a window. This house had been broken up into many apartments before the previous owners returned it to a single family home. This door had once provided access to one such apartment.

Though we temporarily removed the wall between the two parlors, to be re-built as we moved forward, we discovered that the original pocket doors, tucked in during the fire, had survived without any of the charring that the other doors in the house had suffered. They would be salvageable. That gave us some amount of celebration, as it would be one less feature to have to re-create. The mantel in that room would also prove to be salvageable.

Up on the roof, things were happening. The charred remains of roof were removed and the hidden gutters were securely attached to the new perimeter structure. The supporting structure for the SIPS panels was being put into place.

Up here, you could not escape the enormity of what had happened here. Below decks, the fresh new joists and studs, the still-fragrant new plywood, and the energy and debris of new construction littered every corner, and filled the house with a renewed sense of purpose and hope. Up here, what remained was the desolate and scarred skeleton of the house, a surreal landscape of trees and sky where wood and windows should have been. The flayed and blackened ruins peeled back to reveal the ancient internal structures still standing despite their torment. Here, a layer of soot was permanently baked onto the surface of the brick and the remaining darkened window frames were all that was left of any flammable material. It was sobering after the progress below to see the bare bones which was all that was left of the roof.

The view out back was tremendous, you could see the mountains in the background, and a sea of trees and tranquility. Ms. Terry’s garage only added to the sense of timelessness of this view.

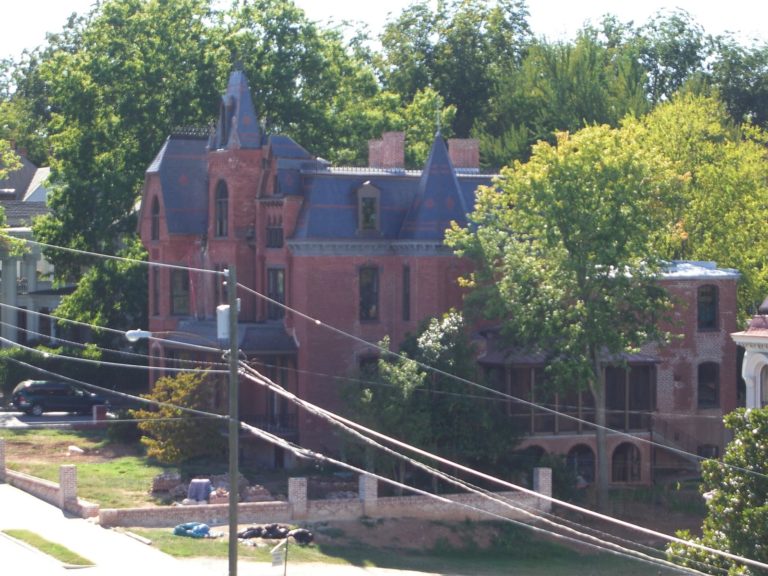

Across the street, the steamboat -like appearance of this Victorian beauty stood out against its neighbors.

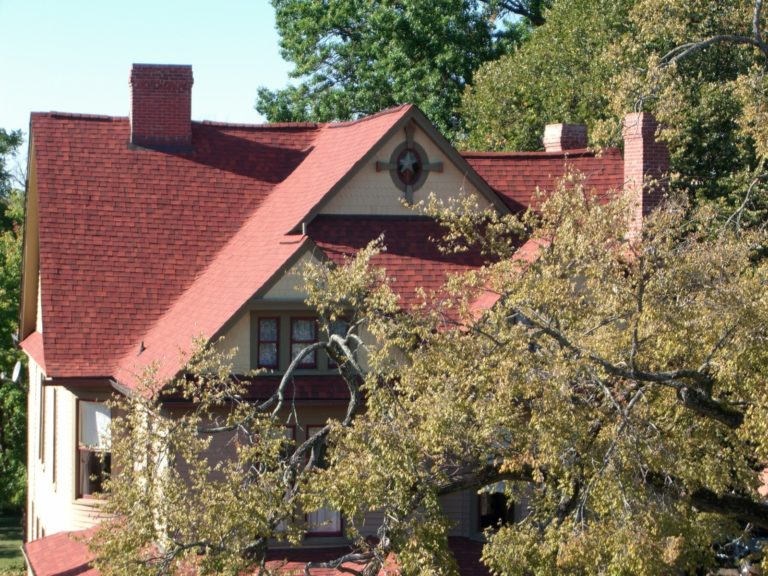

The juxtaposition of Victorian, shoulder-to-shoulder against a foursquare provides interest in the architectural character of neighborhood.

Meanwhile, the four-story tower of the Penn House hovers over the enormous magnolia in the front yard. The myriad of gables, angles, roof lines, chimneys and various windows make it appear more like a little city than a single-family home.

Just up the street, our own house can be seen, the wall for our front yard fence is in the process of being constructed, with re-pointing of the bricks in the rear portion of the house still in progress.

Looking down the street an array of rooftops peeking out behind one grand old Victorian belie the presence of a whole neighborhood of such enormous and beautiful houses.

Just next door, and up the street, the lavender house with its lovely front porch and bold roof stand out in front of the First Baptist Church.

Carla Minosh

While I am new to Blogging, I have always enjoyed sharing the stories of my crazy life, so this is simply another medium to share, and hopefully entertain and enrich others. Perhaps you can feel thankful that your life is so steady and predictable after reading these, perhaps you can appreciate the insanity and wish you had more of it in your life. Either way, the crazy tales are all true (to the best of my spotty recollection) and simply tell the tale of a life full of exploration, enthusiasm, curiosity and hard work. I hope you all enjoy being a part of the journey.

"false sense of history"? No wonder so many are afraid of historical boards and committees, they are the very people that is preventing so many restorations from happening! Bureaucrats! Gah!

You not only have a great story to tell, but you tell it so beautifully.