During the period when I was working part time at the hospital as a CVICU nurse and going to school working on my Masters degree, I received a phone call from Tom one afternoon, asking me what I had on my schedule for the next day. I checked, and let him know that I had a free day, anticipating some adventure that he had concocted. “How do you feel about driving up to Connecticut for the day?” he asked. “Sure.” I replied, and wondered at what he had found. Excited, I made sure to fill the gas tank before heading home.

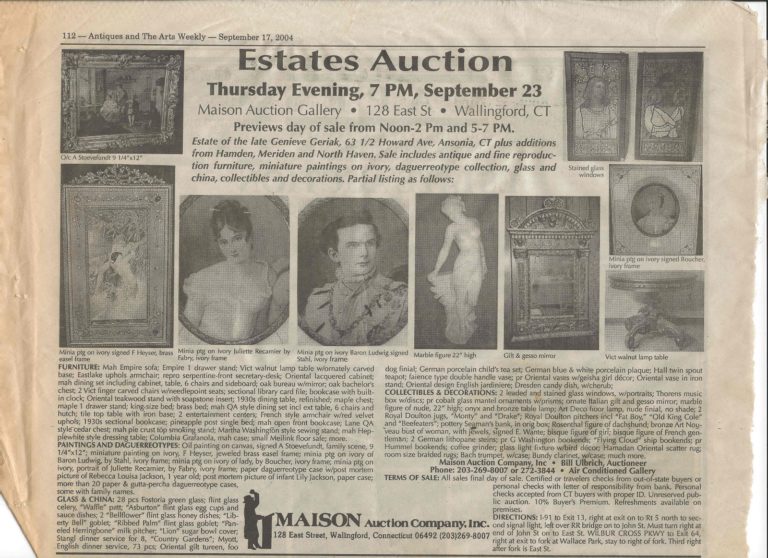

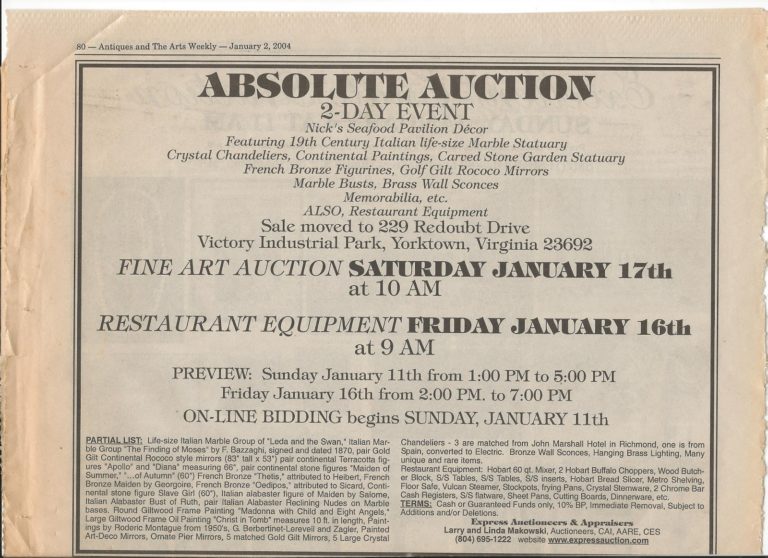

He showed me a black & white advertisement in Antiques & The Arts Weekly which depicted a very small photograph of two stained glass windows. They clearly were Tiffany. Okay, so many of you will look at the photo and wonder what the heck I am talking about — how these two windows can even remotely look like Tiffany through the grainy and miniscule nature of the photographs. Quite simply, the answer is experience. Let me explain…

Years ago when we first became fascinated with Tiffany stained glass windows, we purchased a copy of Alastair Duncan’s “Tiffany Windows” which had an index in the back listing every documented Tiffany window that the author was able to find. This included windows in churches, cemetery crypts, residences, and buildings both public and private. We kept a copy of this book in each car, and throughout our treks up and down the East Coast visiting family, looking for antiques, attending auctions, and day-tripping, we stopped by to look at any nearby window listed in that book. This meant years’ worth of time pressing our noses against the narrow panes of glass of locked church doors to examine the treasures inside, straining our eyes to see what we could from such an inadequate vantage point.

We stood beneath second- and third-story windows squinting to try to take in the lines and colors of the composition, imagining what the windows looked like from the inside, with the light streaming through them.

Occasionally we would get lucky and be allowed into a church if we found the office staff in residence. Either they took pity on us, or thought we were crazy, or were simply investigating the strangers lurking about their building, we didn’t care so long as we were allowed access. It was a treat to be able to view windows from the inside of these churches after seeing them from the outside, trying to make sense of the outlines of figures and the multiple layers of glass obscuring the true design.

We visited every public building or mansion tour we could find where original Tiffany windows were still in place, taking in the beauty of the surroundings in combination with the artistry of the lighted jewels before us.

There were a few excellent stained glass manufacturers around the turn-of-the-century, and in the beginning we would stop outside many buildings and churches, certain that the forms we were seeing from the outside would turn out to be Tiffany when viewed from the inside. We were often wrong. Over time, however, we were wrong less and less often as we schooled our eyes and saw more windows in person, learning the differences between scale, composition, color choices, glass textures, and style of the various glass designers and manufacturers.

Indeed, we even began to be able to differentiate between the evolution of Tiffany’s own windows. It was now clear to us whether a window was produced during his early years, during the heyday of his production, or during the declining years. A 1900 window was as different to our eyes as a 1915 window; as different as a 1955 Cadillac would be to a 1970 Cadillac for anyone who grew up seeing the progression of Cadillac models.

Our favorite churches were ones who would add one window at a time after raising money for production and installation. In these cases it was like history in the making, with the windows at one end being of a completely different vintage to those at the other. One such example of this, and one of our favorite churches, is the Arlington Street Church in downtown Boston on Boylston Street. You can see the slow decline in quality as the windows were added, from 1988 through the late 1920s as Tiffany became less personally involved in the production of the windows produced by his Studio.

As you can imagine, we blended our love of Tiffany Studios with our obsession with architecture, seeking out not only the churches with Tiffany-designed interiors, but also other buildings with interiors designed by this artistic master.

Louis Comfort Tiffany was the son of Charles Lewis Tiffany, founder of Tiffany & Company (I doubt any reader can separate that particular shade of “Tiffany Blue” from the brand of jewelry it represents). Born into such wealth, Louis was able to pursue his love of art, traveling all over the world and honing his painting skills as well as learning from other artists. He was also schooled in his father’s workshops experimenting with silver, gold, copper, and enamels.

Louis loved the way the ancient Roman glass looked, with an iridescent luster born of centuries of chemical change brought about by impurities in the glass oxidizing and reacting to heat and light. Along with another artist, John LaFarge, they experimented with molten glass, adding chemicals and changing the temperatures to attempt to re-create that look. The result was a brand-new product, a glass with that iridescence, that shimmer, with variations in tone throughout the piece. He named this new opalescent glass Favrille Glass and began producing decorative glass objects, as well as sheets that could be cut and made into stained glass windows.

He also discovered that by adding layers of different colored glass in front of or behind a composition, he could create subtle shadings to depict shadows, or create a color change that could not have been achieved with a single piece. He also found that if he pulled and rippled the molten sheets of glass as they cooled, he could create the illusion of drapery or feathering in the panel. He single-handedly propelled an art form which had existed unchanged for centuries, onto a higher plane than any stained glass artist past or present could ever have imagined.

He was painting with glass. His compositions were fluid, His figures lifelike, and his backgrounds lush and colorful. He forever shattered the concept of the stiff saint in red and blue, yellow and green panes, their frozen bodies transected by random lines, faces cartoonish in black paint. Instead he created Angels in flowing robes, expressive faces emitting a light that seemed to come from within them. Churches would never be the same again.

His initial venture was with a small company of artists, furniture designers, fabric designers, and decorators called Associated Artists. Here, along with the likes of Candace Wheeler, Lockwood de Forest, and Samuel Coleman, he designed interiors for residences of wealthy patrons, as well as many of the important rooms in the White House.

Unfortunately, many of these interiors, including those in the White House were lost to more “tasteful” and “modern” upgrades after the 1930s when such opulent interiors went out of fashion. As a result, very few original or restored interiors still remain. One favorite of ours has always been the Park Avenue armory in New York City, the annual venue of the Winter Antiques Show, one show we try to make it to every year.

Our other favorite is the restored Mark Twain house, the Hartford, Connecticut, home of Samuel Clemens and his family. Though the house was once used as a library and a rooming house, it was eventually preserved as a house museum with an ambitious restoration which peeled back years of redecorating to reveal the original Associated Artists work underneath. The restorers were guided by period photographs, as well as the recollections of Katherine Day, a wealthy patron linked to the Clemens family. She had spent some years living in the house, leasing it from the Clemens while they were living in Europe. She compiled her “Reminiscences” of every detail she could remember about how the home looked during the Clemens’ tenure in order to help guide the restoration efforts.

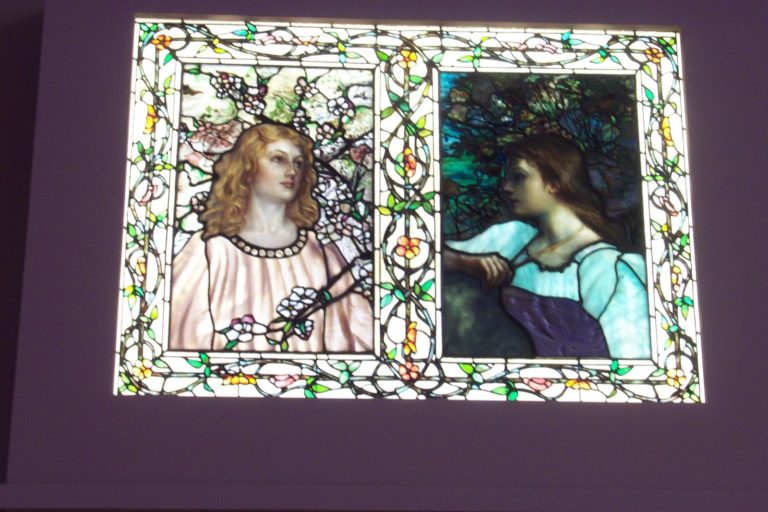

Our first trip to the home left us full of delight at the beauty and history of that incredible home. Add Victorian “steamboat” style architecture to that mix, and we were in heaven. The only thing missing were the Tiffany stained glass windows. During the guided tour, our direction was called to an empty space above the fireplace in the main hallway once held a figure of a woman, “Autumn”, surrounded by fruit and flowers. It had been removed and sold in 1902 when the Clemens’ decided to sell the home, and had never resurfaced. We stood before that blank space and wondered, imagining what it would be like to discover Mark Twain’s lost Tiffany window.

As I made my way up to the auction, I longed to stop by Hartford for another visit, but I was on a mission to get to the preview with enough time to properly evaluate the windows.

I arrived at the auction venue, a moderate single-story building, likely an old retail store, with meandering rooms and a drop ceiling. The windows were not hard to find, hanging aloft over the typical estate auction clutter of dressers, carpets, lamps, chairs, antiques and decorative items.

Rigged to the ceiling with a metal wire, each of the pair hung separately above a large piece of furniture. Since viewing both sides required walking around this piece of furniture, folks were finding it easier to just reach up and grasp the bottom of each window and twist it around so they could see the reverse. I had respectfully circled the bulky buffet enough times to convince myself that this was real, and indeed I was staring at two beautiful stained glass windows designed and constructed by Louis Comfort Tiffany. After taking my seat within view of these beauties, I cringed each time someone spun the pair casually about, back and forth, back and forth, and wondered at the metal fatigue properties of that particular wire thickness. I was relieved when the auction began and the preview area was emptied of people.

I waited nervously until the lot number was called, and promptly got Tom on the phone so that he could be part of the experience. Incredibly, the auction house was treating these two as run-of-the-mill stained glass windows and started the bidding appropriately. I stuck my bidder card in the air and held it there as the tiny increments being called out by the auctioneer slowly crept upward. I remember the usual murmurs which typically create the background noise of any auction house started to go silent at first, then a louder more intense buzz and murmur took over as the bidding went on and on, increasing in $50 increments. It was almost as though the auctioneer were merely counting aloud. This was clearly a disruption to the easy and quick flow of the cadence of the auction, and people who had previously not been paying attention sat up and took notice of what was happening.

I knew where I was in the bidding, my card still in the air, as the auctioneer would raise the amount and point to me after each time another bidder in the room counter-bid. My bidder card was held high and unwavering. Suddenly it was as though the auctioneer understood that more than one person in the crowd saw these as something more than he had recognized them to be, and started increasing the bid increments. Now we were bidding again in silence as the perplexed audience watched the battle intensify and unfold. As I was seated in the front row, I was heedless of what was happening behind me. I figured that the maximum bid that Tom and I had discussed before the auction would either buy this lot or I would go home empty handed. Nothing else really mattered at that point. Tom knew it too; there was silence on his end of the phone.

Suddenly I realized that the auctioneer had called out my maximum bid. I still held the card aloft, never having lowered it, and knowing that one more counter-bid would lower my hand. He repeated the same bid, and again repeated it. My heart was hammering in my chest and my attention was focused on nothing but the auctioneer. Hope surged as I realized he was scanning the audience, a sure sign that my competition had obviously given him a signal that he had declined to counter-bid, and the auctioneer was now looking for another potential bidder. Fear held my breath with an icy grip, as I knew from experience that until the hammer fell, anything could happen. My card was still held high as a challenge to any other bidder, even though I knew it was an empty challenge. Incredibly, the hammer fell. The lovely Tiffany ladies were ours! I remember applause and the person next to me slapping me on the back as the one on the other side shook my hand. Neither had taken any notice of me during the auction up to this point. I said my goodbyes to Tom on the phone after a quick murmur of happy congratulations, and headed for the cashier.

A curiosity of that evening is that I had brought a number of cashiers checks with me totaling our maximum potential bid, plus buyers premium and tax. It was exactly what I paid at the cashier’s desk. I was beginning to get a strange feeling as though somehow this was meant to be, especially since I had mostly expected to leave the auction quietly, using the long drive home as time to come to grips with having seen such beauty first-hand, only to know it was out of reach.

On my way out, a few of the other auction-goers congratulated me, a few asked me some brief uninspired questions, and some murmured to each other about how the windows weren’t even signed. I’ve always wondered how that makes a difference, as the composition and execution of an artists work is their signature, not the little scribble in the corner. I have always felt that the only purpose of the signature is for the people who don’t have a clue what they are looking at, in order to reassure themselves that they have something of value, or as a tool for forgers and crooks to deceive people. To my eye, these windows were screaming the name “Louis Comfort Tiffany”. A signature was irrelevant.

One auction-goer approached me and said he had been seated next to my competition in the audience, two guys who were there together. He told me that these two kept calling these the “Mark Twain” windows, and he thought I should know, in case I didn’t. I thanked him, perplexed and amused. They couldn’t be the Mark Twain windows — these were just a couple of lovely Tiffany residential windows. We would probably never be able to trace where they came from, that’s just the way it was with such things. I had already dismissed this in my mind and didn’t mention it to Tom as we chatted over the phone as I made my way carefully home with my precious cargo.

Upon arriving home later that night, Tom asked If I had talked to my competition at the auction. I hadn’t even seen who I was bidding against, though. It turns out that earlier that evening, after the auction, he had gotten a call from a West Coast Tiffany dealer we knew who had demanded to know if we had bought the windows at the Maison Auction. He was angry and upset. His pickers at the auction had gotten cold feet and hadn’t bid to his maximum. They told him that their competition, the successful bidder, was a woman with unusually long, dark hair, and he could only think of one person interested in stained glass windows who fit that description. He offered to pay us our purchase price in exchange for just one of the windows. Tom had politely declined, but now he was interested as to why this California dealer was so upset over losing these windows. We had seen his collection of Tiffany windows, and certainly these were just small jewels compared to the outrageous and intricate treasures he already owned.

That is when I wondered aloud about the Mark Twain connection, and Tom stared at me for a few long moments before marching off to the bookcase. Dumping a pile of books on the dining room table, we began thumbing through them. He fished Alastair Duncan’s worn and dog-eared book from the pile and began turning the pages. At length he stopped, smiled, and turned the book around for me to see…

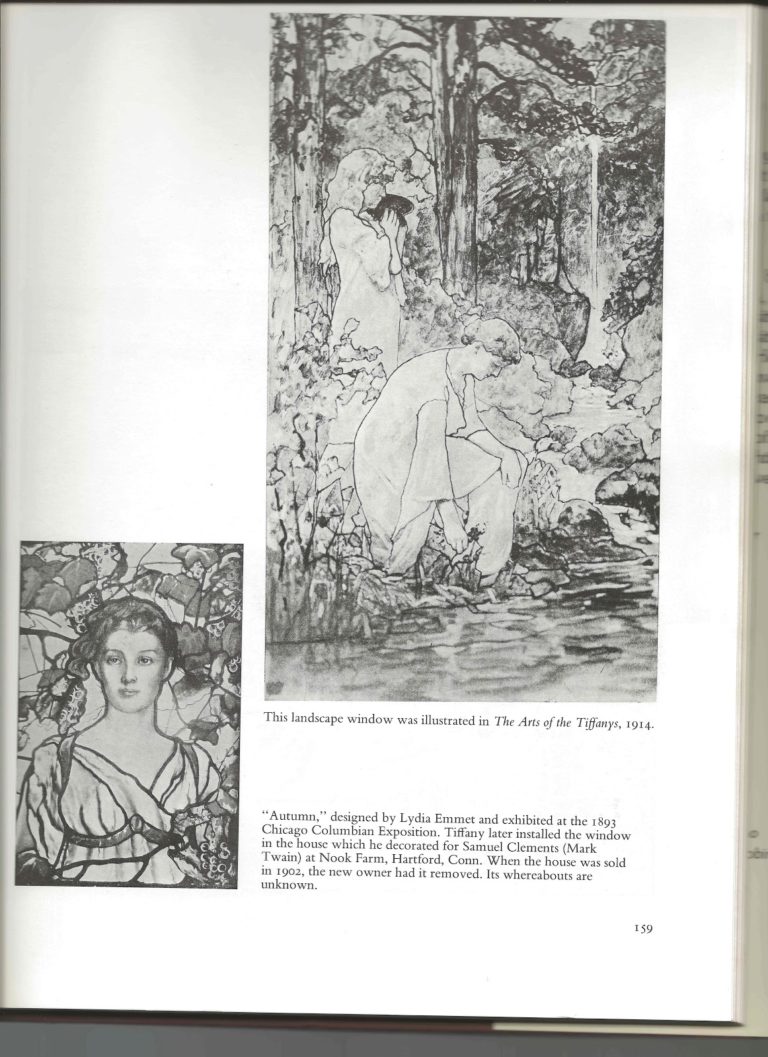

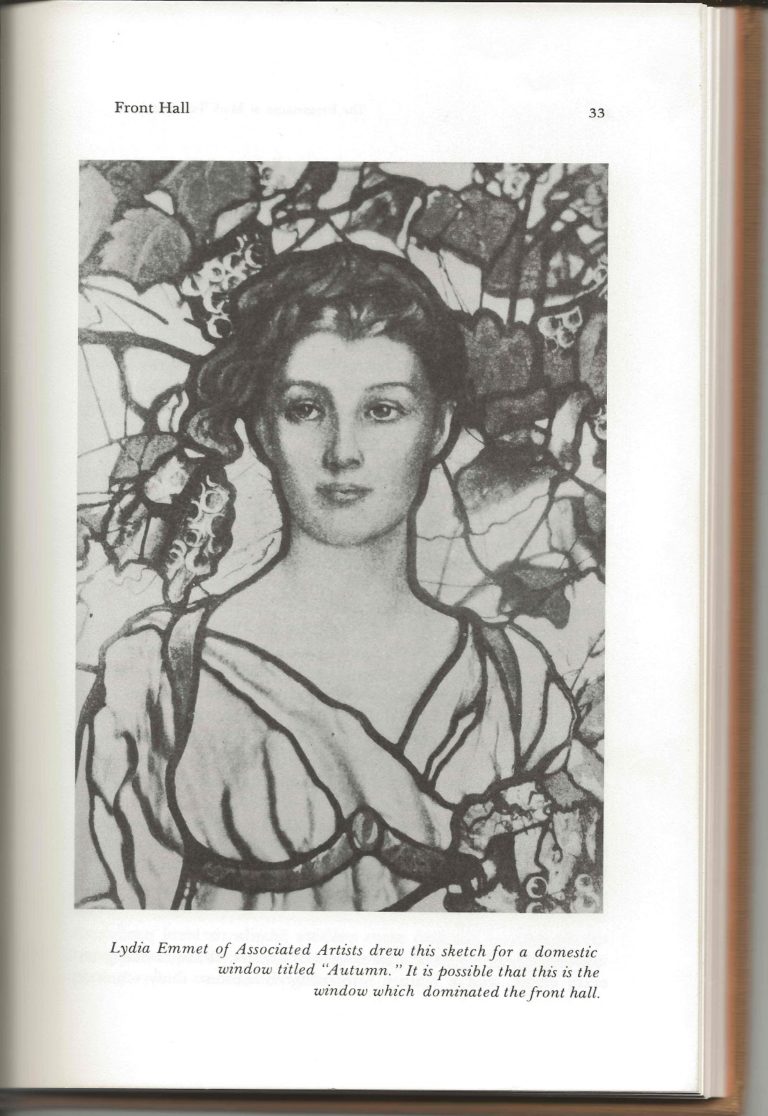

Though the picture in the book is a drawing (or “cartoon”) which is the design for a window, the similarity between the drawing and the window in our possession was remarkable.

And so began my often-frustrating quest to determine the true history of these windows. I started with the auction house, which put me in touch with the consignors of the windows, heirs to the late

Genieve Geriak of Ansonia CT. They were the niece and nephew of Genieve, a brother and sister in their late 60s. They told me that the house in Ansonia had been in their family since 1916, and that the windows were discovered behind a dresser when they cleaned out the house after their aunt’s death. No‑one knows where they came from or how long they had been there. Later research on the Geriak family led me with no further information other than the fact that the family, originally from New Haven, CT, had moved to Ansonia.

I did, however, find an interesting reference to an out-of-print book entitled “The Renaissance of Mark Twain’s House” by Wilson Faude, and promptly located and ordered a copy. In the meantime, I spoke with author Alastair Duncan, who could not recall how he had made the connection between that design by Lydia Emmet and the windows installed in the Mark Twain House.

I looked at old photographs of the 1893 Columbian Exposition, and found some small, grainy photographs of the reverse side of the windows in the Tiffany exhibit. Indeed, they were an “Autumn” and a “Summer” but their patterns did not match exactly with the windows in our possession.

Interestingly, I found a reference to another set of “Autumn” and “Spring” at the Delaware Art Museum in Wilmington. These windows were from Rockford (now demolished), the Wilmington house of Samuel Bancroft, whose collection of Pre-Raphaelite paintings are now owned by the Delaware Art Museum. The windows, installed in an addition to the house in the early 1890s, show Tiffany’s characteristic “drapery” glass and chunks of jewel-like clear glass. The heads of the figures are painted realistically in detail, and the two panels represent the seasons, Spring and Autumn. Though there is some speculation that these windows may have been exhibited at the 1893 Chicago Exhibition, they also do not match up with the photographs of the exhibition.

My search also took me to the Lightner Museum in St. Augustine, Florida. They, too had an “Autumn” window. The home that it had been removed from was identified, and was not the Mark Twain house.

In the meantime, my copy of “The Renaissance of Mark Twain’s House” finally arrived, and I flipped through the pages looking for any information I could find regarding the stained glass windows, until I finally found what I was looking for.

Again, the references were steering me in the direction of the Mark Twain house. I finally couldn’t ignore the obvious and made the phone call to the Mark Twain House and Museum. I spoke with the curator about what the Tiffany windows looked like. He directed me to “Reminiscences” written by Katherine Day. She leased the house after 1891 when the Clemens family was away in Europe. In Reminiscences, she speaks of the a stained glass window over the fireplace in the drawing room, an allegorical figure of “Autumn,” a woman surrounded by fruit and flowers, just like “Summer” in the dining room. This took me by surprise, as any reference I had seen to this point only spoke of “Autumn” and this was the first reference to “Summer” that I had heard of. And we had two windows…”Autumn” and “Summer.”

The curator promptly dashed my hopes, however, telling me that the windows they have documented that were installed during the 1881 Associated Artists renovation, were simple geometric windows. He did indulge me, however, and measured the plate glass in the dining room. It would perfectly fit the “Summer” window in my possession. One thing remains indisputably clear, however; the stained glass windows that were in place during the tenure of the Clemens family were removed in 1902 when the Clemens’ decided to sell the house after the death of their eldest daughter, Susy.

Thus far, the mystery still remains. Why remove and sell simple geometric windows before selling your house? This action would only make sense if the windows you are removing have great value that would be otherwise lost — especially important for the cash-strapped Clemens family at that time. Also, it was not uncommon to install simple geometric windows as a placeholder while more elaborate windows were being designed and constructed, a process that could take some time. Perhaps the ultimate windows in the house were indeed the figural ones that Katherine Day recalls from her days living in the home.

I also have the misfortune of researching a subject that leaves itself with few resources. Photography at the time was still in its infancy, with long shutter speeds limiting the subject matter of photographs. Too much light would overexpose the film, so photographs of stained glass windows are practically nonexistent, unless they were photographed in a lighted room at night. The other problem is that if one had a camera and were visiting the home of the legendary Mark Twain — where would you be focusing your lens? On the Man, of course!

Exterior pictures of the home are also obscured. Though the drawing room window was an interior window, the reverse side looked out into the main hallway; the dining room window could be seen from the exterior. Unfortunately, it was placed on the least picturesque side of the home, and was obscured by a large tree. So much for seeking guidance from the period exterior photographs of the place.

My job now is to wade through the mountains of correspondence in the possession of the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley to discover what actually transpired between the 1881 Associated Artists decorations and 1891 when the Clemens family left for Europe, never to return to their Hartford home again.

Personally, my instincts are to believe Katherine Day, as she provided a firsthand account of her memories of having lived in the Mark Twain house, for the sole purpose of restoring the house to its’ former glory as she led the preservation group through its’ purchase and early restoration efforts. I have every expectation that the correspondence discussing these potentially-important windows will one day surface. In that case, it would be amazing to see these girls back in their rightful home one day. In the meantime, we can continue to enjoy the beauty of these two allegorical figural windows in our own home. Now that I think of it, they do look a lot like Samuel Clemens’ daughters, Susy and Clara…

Carla Minosh

While I am new to Blogging, I have always enjoyed sharing the stories of my crazy life, so this is simply another medium to share, and hopefully entertain and enrich others. Perhaps you can feel thankful that your life is so steady and predictable after reading these, perhaps you can appreciate the insanity and wish you had more of it in your life. Either way, the crazy tales are all true (to the best of my spotty recollection) and simply tell the tale of a life full of exploration, enthusiasm, curiosity and hard work. I hope you all enjoy being a part of the journey.

There is a similar window to "Summer" in the Driehaus Collection in Chicago. That one is called "Girl with Cherry Blossoms" (but I don't know whether that was the original name). A photo of it can be seen here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Girl_with_Cherry_Blossoms_-_Tiffany_Glass_%26_Decorating_Company,_c._1890.JPG

or in shorter form:

http://tinyurl.com/o2oevav

There is an 1893 Architectural Record that shows a cartoon and window for Autumn (Fall) on pages 488 and 489:

http://ia700304.us.archive.org/23/items/architecturalrec02newyuoft/architecturalrec02newyuoft.pdf

That says that Rosina Emmet [misspelled as Emmett] Sherwood was the designer, not her sister Lydia, but that could of course be wrong.

Wow. Fascinating (and informative) post!

One would have to use common sense on this mystery! As was said why would a cash strapped person focus on pulling two windows out of a home that obviously had other windows worth a lot more at that time??

Remember these weren't collectible windows yet….it that era these were just used old windows that could be had at a salvage yard…..BUT if we think now…the only reason to remove these windows is if at the time the subjects used for the windows were actually family relatives….thus these windows would have value to the family as heirlooms….

Looking at Samuel Clemens' daughters pictures and the photos of your windows; I would say dead on they are of her daughters…thus the reason for removal!!!

If you are ever in or around the St. Augustine Florida area you must visit Flagler College (formerly the Ponce de Leon Hotel) and the Lightner Museum, housed in Henry Flagler's less lavish (but still pretty darn fancy) Hotel Alcazar.A place that is rich in history, there you will find a treasure trove of L. C. Tiffany stained glass, lamps, chandeliers, clocks, etc,, as well as many other Gilded Age art and antiques.If you go to this Facebook page and scroll through their cover photos, you can get an idea of the beauty you will encounter there: https://www.facebook.com/HistoricalToursofFlaglerCollege

What a find! I think I'd have needed a nerve pill. I know I'd have needed a nerve pill.

By chance do you know is that the Katherine Day ( Katherine Briggs Dodge Day) that married Clarence Day? I am trying to tell by dates but the internet is not working with me. I'm just curious, Clarence Day is one of my favorite authors.

Katherine Seymour Day, grand-niece of Harriett Beecher Stowe who lived next-door.

Great article. I have heard the people at the mark twain house say many conflicting things about this area. Totally makes sense that associated artists would install a window in this space as they always seem to be installing art glass in their work between 1879-1883. Tiffany even experimented with glass in his studio prior to that partnership. I would love to talk to you more. You seem to share a strong passion like me.

I've read The letters with Sam's wife Livy to Whitmore, who was supposed to be removing the contents and she does speak of several stained glass windows and how they can remove the windows without it affecting the glass behind them. Because if she remembers correctly they were simply bolted over the windows behind them and should not be a problem for the new people that moved in. Some of the Mark Twain House thinking is that this geometric shape the windows resembled the ones in the park armory which are even though geometric shapes are beautiful. I have several pictures of the Mark Twain House there is one in particular or you could see the dining room window. And it's from soon after they put the addition on the house.

any idea what happened to the Girl on a crescent?

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.