The Victorian era produced beautiful cottages, homes, mansions, and even a few castles across the landscape of America. In addition to their grace, character, and beauty, the one thing that all of these new buildings had in common was their devout attention to detail. The new-found wealth of America was being poured enthusiastically into these new structures, lovingly constructed and solidly built; this country had never seen anything quite like this before. Forget the stark simple Puritan lines; ignore the symmetric rules of Palladianism; step outside the monotony of the Georgian; and steal liberally from the Neoclassical and the Ancient Greeks.

Some examples in Danville…

Refusing to follow in the Federal footsteps of their forefathers, the children of the Victorian era gazed along the length and breadth of the known world and all of its history and re-imagined architecture in a way that paid tribute to all architects who had ever come before. They incorporated forms newly-discovered in the Orient. The Middle East and the Far East had found a new market, and the influx of furniture and art objects arriving from that continent were captivating the imagination of Americans. In addition, they continued the traditions brought to them from Europe and the Mediterranean, but incorporated them alongside these new styles and in a new manner.

More Danville exuberance…

From the turnings on the porch, the decorative corbels, the massing of the towers and the turrets, to the details in the decorative window trim and scalloped slate tiles lining the roof; these homes were all about the “wow factor.” And the “wow factor” continued on into the interior of the home itself. Many grand homes boasted two sets of front doors, an outer set, typically constructed of solid wood separated by a vestibule space and flanked by an inner set of doors, often with glass windows or stained glass. Though it seems excessive to have a space devoted to the separation of two sets of doors, the simple entry space of a vestibule allowed for a practical place for mud to be shaken off of boots and coats removed with the dust of the road still upon them. If you consider the state of most roads during the period, it only makes sense. The durability of the flooring put down in most vestibules attest to the hard use intended for these spaces.

In addition, two sets of entry doors also allowed an extra buffer from the cold during the winter. The other advantage being that the solid wood outer doors could be left open in the Summertime allowing indirect light to filter through the inner glass doors, proving extra light without the extra heat. In many cases, during good weather, having the outer set of doors open was an invitation to visitors; a sign that you were home and you were receiving guests.

Large windows, most often a single “light” (one sheet of glass without any mullions) was also an exorbitant excess considering the cost of glass and the difficulty of manufacturing such large single panes. These were more than just a luxury, however. In the winter, opening and closing the drapes helped regulate the temperature inside by allowing the sun on the southern exposure to radiate in during the cold winters’ day and closing tight the thick curtains against the night in the winter to provide a layer of insulation with the rich fabrics. In Summer, lowering the top sash during the hot summer nights allowed the air trapped at the top of the high ceilings to escape at night as well as allowing the cool evening air to enter and refresh the house, while during the day, the multitude of windows and large lower sashes allowed for a cooling cross-breeze. In addition, such large windows gave light into the dark spaces within the home.

Fireplaces, nowadays seen as simply decorative elements, were the sole source of heat when many of these homes were built. Granted their utility did not require that they be vulgar; though it was necessary for the sake of efficiency that the heat source should command a prominent position in the room. This focal point was simply an invitation, challenging the creativity of the architects and artisans of the day to turn such a necessity into a thing of beauty. Sculpted from marble and carved from wood, layered slate with paint–decorated surfaces; they topped it all with mirrors surrounded by vertical gilded gardens of flowers, vines, and curlicues. Egg-and-dart borders and Greek key patterns went marching around the edges, and they crowned them with putti, eagles, heraldic shields, and swags. The large panes of glass in the grey of these mercury-backed mirrors reflected the light from windows, sconces, and chandeliers, tossing those reflections into the far recesses of the room.

Okay, so maybe the regular crop of bruises which are permanently tattooed on my legs would argue that this is not a new problem for me, but certainly the problem became worse. And so, I turned my face upward and began an even greater appreciation of the beauty hanging overhead, and the many challenges of bringing illumination into such deep and tall cavernous spaces.

We first became captivated with antique lighting even before we had purchased this house. An auction at the Hunter mansion in Tidioute, Pennsylvania yielded a wealth of Victorian furniture. We had been collecting Victorian furniture long before we ever owned a Victorian home; It was tautological that a Victorian would be ours one day. This particular auction, however, presented a mouth-watering array of Victorian pieces in an incredible state of preservation. The preview was held the day before the auction, and was very quiet; I snapped my photos without having to pause too often for other prospective buyers blocking the frame.

Some photos from the auction…

The morning of the auction, however, was complete chaos. Vehicles towing trailers with New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut license plates lined the narrow sloping streets of the sleepy little town making them almost impassable. The sheer mass of humanity crowding the lawn, the barn, and the rooms of the house itself left us quite deflated. We had expected to come away from this auction with quite a number of spectacular pieces of furniture; at this point our luck had run out. We resolved to bid anyway, and decided to stay for the spectacle that the crowd promised.

More photos of the “ones that got away.”

As predicted, we were easily outbid on every…single…piece. The act that caught our attention, however, was not any item we had been interested in bidding on. As the auctioneer began to march the parade of lighting across the “stage” (a section of front porch he had commandeered for the proceedings), he announced the first of the original pieces of gaslighting which had been stored in the barn after the electric lighting had been installed in its place. All of the gas fixtures were in excellent condition, having been packed away safely in crates stuffed with straw and had been stored in the barn loft after their removal. We had never much thought about antique lighting before this, and had not even taken a close look at the chandeliers in their crates, except to gaze at them as objects of curiosity.

As the first enormous bronze chandelier walked across the porch stage, a lean-built strong young man staggering under the weight of the spray of twelve arms. No crystals were to be seen, but rather, spiky angular projections regularly punctuated the vertical stem; the exuberant decoration was clearly making this item a difficult one to grasp. It appeared as though some large alien creature was in a battle to the death with this particular young man. The price was staggering as well, at least at least to our uninitiated sensibilities. A dealer in the front row was the successful bidder, but her card remained aloft even as the second chandelier was being announced and described and was making its way, tottering dangerously in the arms of the next young helper. Again, the same dealer in front was the successful bidder, and still her bidding card was held high in the air. There it remained, unwavering, for the sale of every last piece of lighting that had once been originally installed inside this grand mansion. Only after the last piece was sold did she lower her card; she had bought it all.

I now lament not having any photos of these pieces. As my eye was not trained to find the telltale characteristics of a high-end manufacturer from the Victorian era. In retrospect the gross details in the general forms that remain in my memory speak to the possibility that this was an entire lot of Cornelius or Mitchell and Vance lighting. The prices certainly suggest as much. We were contemplative on our drive up to the Family Reunion, where we were now overdue. In between our lamentations over leaving the sale empty-handed, our talk turned again and again to the lighting and the value that the pieces had commanded. Upon our return home, we began the research that would begin to quench our thirst for knowledge about the spectacle we had witnessed.

It was also not traditional to have a crystal chandelier in the dining room, as much as modern interpretations seem love to place the largest crystal-laden piece they own over the dining room table. According to decorative guides of the period, these glistening frames dripping with icicles were more suited to parlors and music rooms.

We started perusing our auction advertisements in earnest. Even twenty years ago, the antique world was a different market, operating by old-fashioned rules. A small black & white ad in a newspaper such as the Bee or the Maine Antiques Digest (delivered by US mail) would prompt a phone call to the auction house where you would talk to the auctioneer and he would answer any questions. A request for photos would yield some grainy pictures which would arrive in the mail a week later. If this was enticing, and the auction house close, you would attend the auction preview, scheduled some days in advance of the auction, then decide if you wanted to pursue the piece and return on the day of the auction. If the auction was far away, you would show up for the day of the auction and either stick around for the lot, if you wanted, or not, if it didn’t turn out to be as nice as you thought.

A pair that didn’t get away…

Auctions were a long, drawn out affair, and we would sometimes spend an entire day bidding on this item or that while waiting for our ultimate quarry. There were too many mid-sized and small auction houses to count, and independent auctioneers without their own venue were a dime a dozen. There were no phone bids, as cell phones were not as ubiquitous as they are today. In fact, very few mid-sized or smaller auction houses even offered that option. There were no internet bidders, because the newly-budding internet wasn’t what it is today. Google and Ebay were in their infancy, and Artprice.com and Live Auctioneers.com hadn’t been invented yet. There were often no lot numbers; helpers brought items up front in random order. If you weren’t paying attention when your lot came up, it was just too bad.

In addition to the rare auction at a sophisticated and comfortable upscale auction house, such as New Orleans Auction or Neal Auction, we spent many weekends in auction warehouses, unheated barns, disassembled homes, and even outdoor lots. The chairs, if provided, were always cold, metal, and uncomfortable. Since most auction venues were low-rent and were only open on auction days, they were typically miles from any decent food. The food vendors they attracted on auction days generally provided less than appetizing options of cheap hot dogs and cheap hamburger patties on stale buns, with questionable coleslaw and potato salad, overloaded with mayonnaise. Throw in some greasy potato chips, and add the smell of stale cigarette smoke and the stickiness of dried spilled sodas underfoot, and you have the general feel of what most small auctions were like before the days of the internet.

Today we browse the Internet, zoom in and out of dozens of quality digital photos, request a condition report which is promptly sent by email, place a phone bid, and go on about our lives. On the appointed day, we get a phone call and bid on the item, and we follow the bidding on our tablet, knowing if we are bidding against the floor, the Internet, or another phone bidder. Occasionally we go see the piece in person. We rarely attend auctions any more.

In all truth, I occasionally miss the old days; as uncomfortable and inconvenient as they were. If you paid attention, made the effort, and knew what you were looking at, there were some amazing bargains to be had. Competing against the Internet, and dealers who can now bid at auctions across the country without leaving their desk, makes it more difficult to unearth a hidden treasure.

In addition, what was once a relaxing day trip with the family, an exciting adventure exploring small towns and meeting interesting people, pursuing a potential treasure, is now a rapid-paced rational academic and systematic process devoid of human contact. Any sense of excitement happens in such a small window; our anticipation and successes are no longer savored and re-lived on the long drive home. I am truly glad that we had the opportunity to acquire most of the treasures we have at a time where we were engaged in the process in a way that will never be possible again.

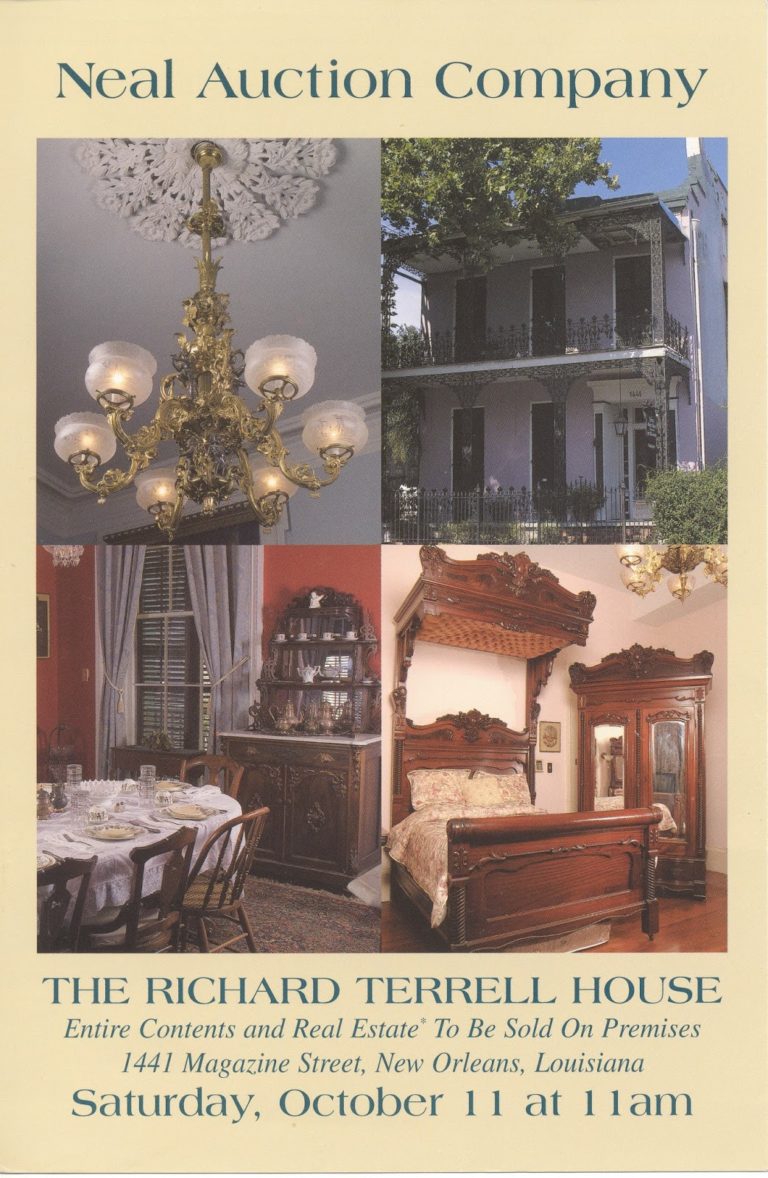

One of our first significant lighting purchases occurred during the transition phase, when the electronics hadn’t fully changed the auction landscape, in 2003. A Bed & Breakfast, the Terrell House, in New Orleans, was going on the market and the owner had chosen to auction off all of the furniture and lighting he had found and had installed in the house when he had purchased it many years before.

There was a period in American history when the beautiful things produced during the Victorian era fell rapidly out of fashion. People viewed the furniture, art, and decorative elements as being too fussy and overdone. Furniture was thrown on the garbage heap, chandeliers cut down and allowed to crash into trash receptacles waiting below, and mantle mirrors removed en masse. Even Tiffany lamps were being smashed on the streets for the salvage value of their lead. The wife of the heir to the New York Vanderbilt mansion, decorated by the prestigious Herter Brothers, declared that the home was the “Black Hole of Calcutta” and immediately gutted it and re-decorated. Even the White House was stripped of its’ Tiffany stained glass, and Associated Artists’ interiors.

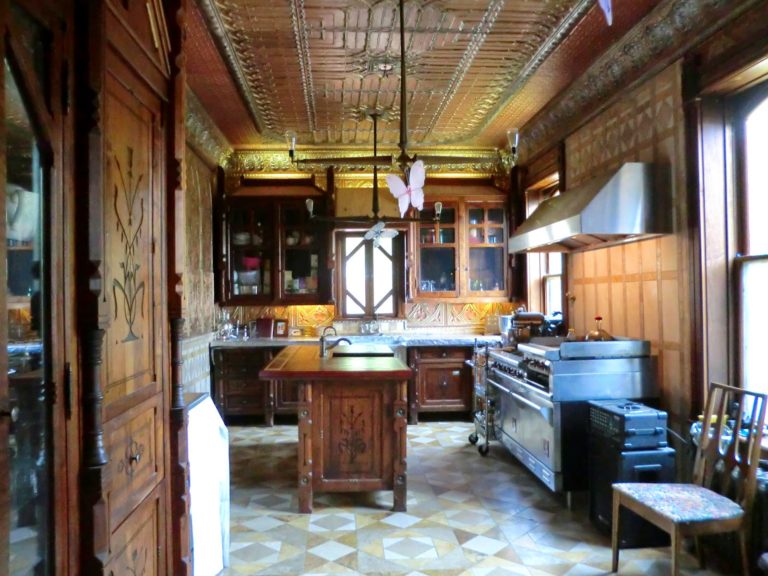

During this period, you could purchase anything Victorian for a song. That is, no doubt, when the owner of this particular B&B made his purchases, because practically every room in this house sported chandeliers and sconces by Cornelius & Company, of Philadelphia, and the furniture was outstanding. This B&B owner had great taste and an eye for excellent design, artistry, and manufacturing. We attended the auction preview and counted up our pennies. We had enough to purchase a matched pair of two large chandeliers, if we were lucky. Since we couldn’t be in New Orleans on the day of the auction, we had a friend bidding for us, and instructions to bid to our maximum on those two chandeliers. If we had anything left over, he would try for a couple of pairs of sconces.

By way of introduction, Cornelius & Company was a Philadelphia establishment of the 1820s, producing gasoliers of all shapes and sizes. In addition to the grand pieces they produced for parlors, theatres, and public buildings, they also produced smaller pieces for newel posts, vestibules, and bedrooms. Smaller tabletop lamps and sconces also came out of their workshops. Though the founder of the firm, Christian Cornelius, started of as a silversmith, he quickly adapted his skills to the manufacturing of lighting. The firm really took off, however, when the City of Philadelphia Installed gas lines to supply the needs of the City’s inhabitants. Chandeliers lit with candles were quickly removed, and replaced by brand-new gas fixtures to take advantage of this modern improvement.

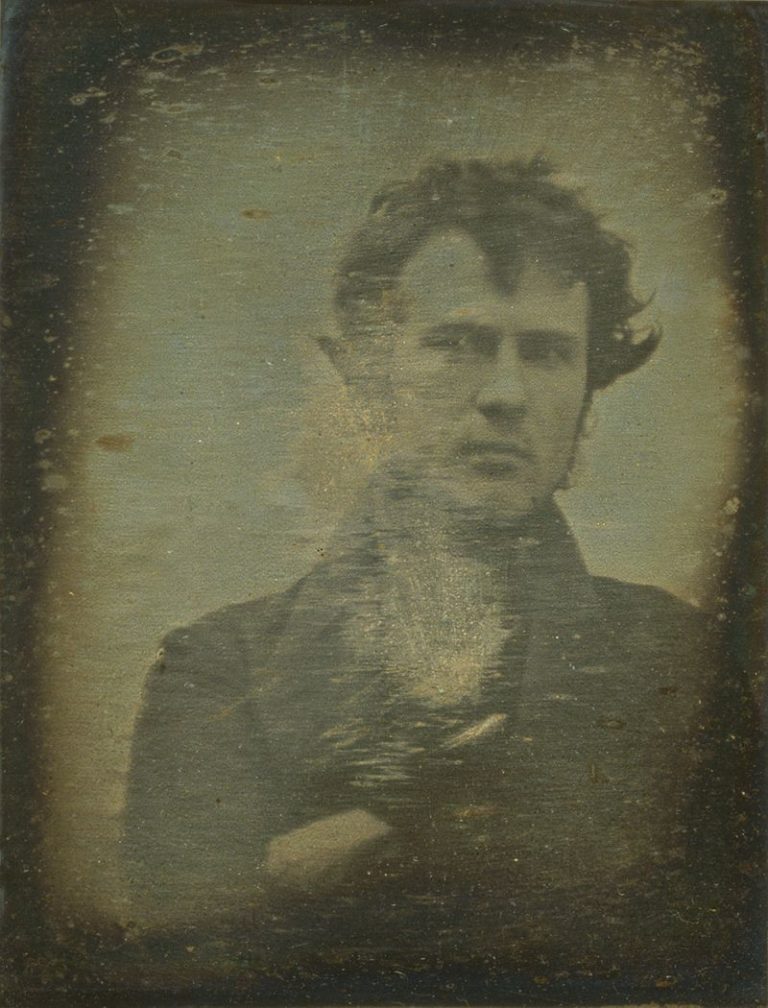

The early firm, known as Cornelius and Company, or Cornelius and Sons, after the next generation came of age to take on the family business, with Robert Cornelius taking over from his father in 1851. It was later to be known as Cornelius & Baker. In addition to producing the finest examples of American lighting during his tenure at the company until 1876, Robert Cornelius was also a chemist, and an innovator in the lighting industry. He held multiple patents for his improvements in modern lighting. His interest in chemistry also allowed him to take advantage of recent improvements in photography, using Iodine and Bromide in the processing, allowing exposure times of 10 minutes to be reduced to a mere 10 seconds. Based on this new technique, in 1839 he was the first to photograph a human face — his own. A selfie, of course! How far we have come in one-hundred-and-seventy-plus years.

At its peak, the firm of Cornelius & Company was producing the finest gas lighting that could be found in the country. As the new wealth of America was being poured into its residences, so also was it being directed at the grand public buildings under construction. By their own measure, the firm was responsible for lighting almost every State building under construction or newly-completed during this period. The icing on the cake, however, was the United States Capitol building, in which period photographs document the enormous chandeliers placed in its halls.

And in the U.S. Capitol President’s Room…

In addition, a pair of the firm’s fixtures were the hung in the State Dining room of the White house, truly a prestigious commission.

Meanwhile, public buildings, opera houses, elegant hotels, fashionable dining establishments, ecclesiastical buildings and prestigious homes followed suit. The pair of chandeliers we wanted were beautiful examples of Cornelius lighting. Identifying them was a no-brainer, as the manufacturer’s name was stamped on the gas keys, not an unusual way to advertise. Though the gilding was a little bright, the finish was not offensive.

The base began simple, almost gothic in form, and quickly turned rococo, with a lower platform of flowers and grasses from which three putti emerged from the center of the piece.

Above the heads of the putti, originating from a ring with gothic elements. At the base of each arm, a feminine face peered out solemnly.

The six arms fanned out in a radius, each arm draped with undulating leaves, the arms themselves in sweeping curvaceous forms that linked together gracefully, the descending curves linking with the rising curve of the next section.

On the second tier, just above where the six arms joined, stood a trio of Indian Braves clad in simple loincloths, each holding a small drum aloft in one hand, beating it with the other, and twisting, dancing with one knee high in the air, leg bent behind them in grace and strength, beautifully balanced. Their braided hair piled atop their heads, their countenances decorated with dangling jewelry. The Indians were each separated by small flowering groups of leaves at their feet and between each Brave, a curvaceous and sinewy creature split the landscape, lacking limbs and bearing a simple shield on his chest, the face of a lion roaring mutely. The Indians danced with substantial fluted column in the center behind them.

Above the heads of the Indians, Larger leaves curved above and behind them, then narrowing to a point only to burst out again in yet another billowing group of foliage and flowers.

Again the whole narrowed to a point before throwing out yet another, more stylized grouping of pointed leaves before the stem of the chandelier began its ascent into the ceiling, above. Even the stem was interrupted, yet again by still another disk decorated with more foliage before resuming its ascent into the final simple ceiling cap. The stem, itself, had an elaborate embossed patter curving around and around it echoing the movement upward.

They were beautiful! It turns out that we were lucky, indeed, and walked away from the auction with the coveted pair of chandeliers and one pair of sconces. Looking back on the photos from the auction, I only wish we had been able to buy it all. Much of it looked like it had come from the same house.

Some of the lighting that got away…

While the pair of chandeliers were undoubtedly Cornelius, it was fun to discover our “Indians” were also used in chandeliers that the Cornelius firm had installed in the President’s Room at the U.S. Capitol. While we could never achieve the scale and decadence of those chandeliers, decorated not only with Indians and putti, but also with historical characters, frontiersmen, and statesmen, we are more than pleased with the treasures that we have.

The pair of sconces were not immediately identifiable to a particular maker, but were of the highest quality. In addition to the myriad of leaves, swirls, and decorative swishes, each had a sheep head with a little bell around the neck of the sheep. It would be fun to dig in and do the research to try to figure out who had made these pieces.

More next time. In part II, I’ll introduce you to some of the other prestigious lighting firms of the day, as well as tour the collection of mantel mirrors. Until then…

Carla Minosh

While I am new to Blogging, I have always enjoyed sharing the stories of my crazy life, so this is simply another medium to share, and hopefully entertain and enrich others. Perhaps you can feel thankful that your life is so steady and predictable after reading these, perhaps you can appreciate the insanity and wish you had more of it in your life. Either way, the crazy tales are all true (to the best of my spotty recollection) and simply tell the tale of a life full of exploration, enthusiasm, curiosity and hard work. I hope you all enjoy being a part of the journey.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.